Last updated: August

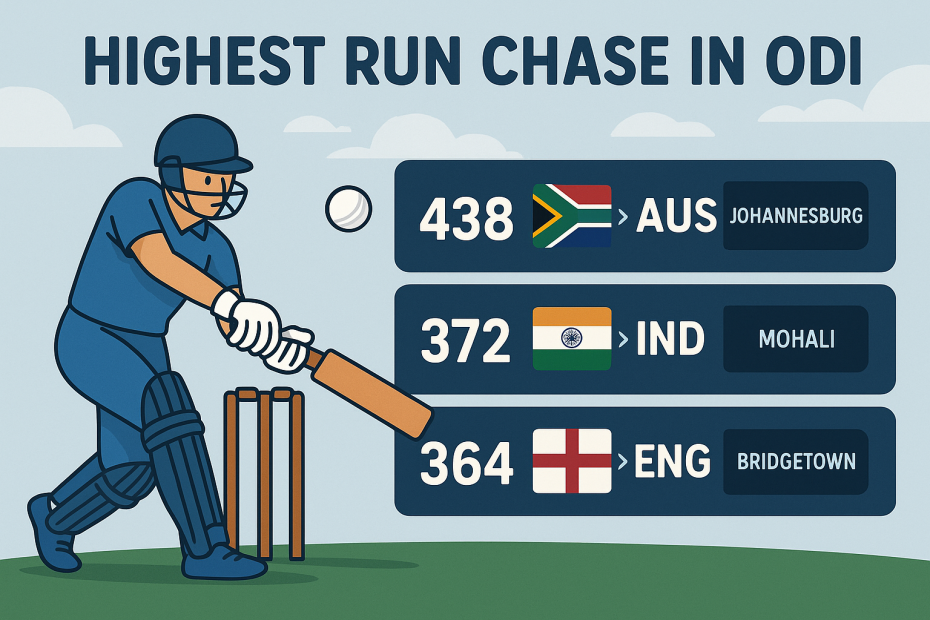

South Africa’s 438 for 9 against Australia at Johannesburg remains the highest successful run chase in ODI history. They overhauled a target of 435 in a match that has since become the compass point for every white-ball epic.

What makes a chase historic has never been just the number. It’s the narrative of calculation and courage, the elasticity of risk under lights, and the way a dressing room reads a pitch and the arc of an innings. Big chases are less a sprint than a precise escalation: the first ten overs set the runway, the middle overs define intent, and the last five are decided by who holds their nerve when every ball feels like a question.

This is a deep dive into ODI’s biggest record chases—full list, team-wise peaks, World Cup landmarks, tactical patterns, and those matches that changed the vocabulary of chasing forever.

Top successful ODI run chases (landmark matches and context)

The matrix below lists landmark chases that shaped the ceiling of what is possible in ODIs. Figures include the chasing score, the target, wickets in hand and overs used, along with where the game was played and who cracked it open with the bat. These are the reference points analysts use when judging whether a modern pursuit is on or gone.

Table: Highest successful ODI run chases (selected top tier)

| Rank | Target | Chasing team | Score | Overs | Venue | Result | Standout batters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 435 | South Africa | 438/9 | 49.5 | Johannesburg | South Africa won by 1 wicket | Herschelle Gibbs 175, Graeme Smith 90, Mark Boucher 50* |

| 2 | 372 | South Africa | 372/6 | 49.2 | Durban | South Africa won by 4 wickets | David Miller 118*, Quinton de Kock 70, Aiden Markram 74 |

| 3 | 361 | England | 364/4 | 48.4 | Bridgetown | England won by 6 wickets | Jason Roy 123, Joe Root 102* |

| 4 | 360 | India | 362/1 | 43.3 | Jaipur | India won by 9 wickets | Rohit Sharma 141*, Virat Kohli 100* (off 52), Shikhar Dhawan 95 |

| 5 | 359 | Australia | 359/6 | 47.5 | Mohali | Australia won by 4 wickets | Peter Handscomb 117, Usman Khawaja 91, Ashton Turner 84* |

| 6 | 359 | England | 359/4 | 44.5 | Nottingham | England won by 6 wickets | Jason Roy 114, Joe Root 43, Jonny Bairstow 51 |

| 7 | 351 | India | 356/7 | 48.1 | Pune | India won by 3 wickets | Virat Kohli 122, Kedar Jadhav 120 |

| 8 | 350 | England | 350/3 | 44 | The Oval | England won by 7 wickets | Joe Root 106, Eoin Morgan 88 |

| 9 | 349 | Pakistan | 352/4 | 49 | Lahore | Pakistan won by 6 wickets | Babar Azam 114, Imam-ul-Haq 106 |

| 10 | 348 | New Zealand | 348/6 | 48.1 | Hamilton | New Zealand won by 4 wickets | Ross Taylor 109*, Henry Nicholls 78, Tom Latham 69 |

| 11 | 347 | New Zealand | 350/9 | 49.3 | Hamilton | New Zealand won by 1 wicket | Craig McMillan 117, Brendon McCullum 86 |

| 12 | 345 | Pakistan | 345/4 | 48.2 | Hyderabad (India) | Pakistan won by 6 wickets | Mohammad Rizwan 131*, Abdullah Shafique 113 |

| 13 | 344 | South Africa | 347/5 | 49.1 | Potchefstroom | South Africa won by 5 wickets | AB de Villiers 92, Hashim Amla 97 |

| 14 | 343 | Sri Lanka | 344/4 | 37.3 | Leeds | Sri Lanka won by 6 wickets | Sanath Jayasuriya 152, Upul Tharanga 109 |

| 15 | 339 | India | 340/5 | 49.3 | Cuttack | India won by 5 wickets | Virat Kohli 122, Kedar Jadhav 52 |

| 16 | 338 | South Africa | 340/5 | 48 | Bloemfontein | South Africa won by 5 wickets | AB de Villiers 73*, Graeme Smith 84 |

| 17 | 336 | England | 337/7 | 49.3 | Nagpur (neutral series) | England won by 3 wickets | Owais Shah 98, Paul Collingwood 91 |

| 18 | 332 | India | 338/4 | 48.5 | Jaipur | India won by 6 wickets | Rohit Sharma 141, MS Dhoni 85* |

| 19 | 331 | Bangladesh | 322/3 | 41.3 | Taunton | Bangladesh won by 7 wickets | Shakib Al Hasan 124*, Litton Das 94* |

| 20 | 329 | Ireland | 329/7 | 49.1 | Bangalore | Ireland won by 3 wickets | Kevin O’Brien 113 |

Notes for context

- Targets and totals listed here come from authoritative scorecard archives and match databases used by analysts for cross-era comparison. A handful of the entries above double as national records for the chasing country and are cited again in team-wise lists below.

- The exact order of ranks beyond the first tier can change as new series and tournaments produce fresh data. The matches included here are the cornerstone chases around which modern chasing tactics are still taught.

Why the 438 game stands alone

At first glance, the winning score is a statistical freak. But the greatness of 438 lives in the chase craft. South Africa didn’t simply swing wildly at Johannesburg; they made several courageous, micro-correct decisions as the game oscillated:

- Up top: Smith and de Villiers weren’t chasing run rate; they were chasing momentum. Powerplay lengths and fields mattered. They forced Australia to defend the short square boundaries early, which lifted the par trendline for the entire innings.

- Gibbs’ decision point: After a tricky start, Gibbs’ shot selection accelerated through the V and leg-side pockets. He treated the high back-of-a-length stuff as scoring balls, not just dots, relying on the altitude and the white ball. That broke the typical middle-over choke.

- The spin window: Australia held back overs for Bracken and Lee; South Africa refused to give cheap wickets to spin. Every run against spin dragged premium pace overs into a tighter death-phase window.

- Death math: The Boucher-Hall and Boucher-van der Wath stands re-centered calculations. They didn’t chase a number; they chased a makeable last two overs with access to both short sides of the ground.

It wasn’t a one-off miracle. It was the first global demonstration that a target above 400 is not a knockout if your batting order is long enough and your intent is coherent.

Highest ODI run chases by team

Every national side builds its chasing personality around conditions, batting depth, and captaincy style. Some teams lean on set patterns; others ride the improvisational genius of a couple of hitters. Team-wise peaks tell that story.

– South Africa

Highest successful chase: 438/9 vs Australia (target 435) at Johannesburg.

Signature traits: aggressive powerplay batting, high-value boundary options square of the wicket, and late-overs trust in hitters who find the gaps rather than just clear the ropes. South Africa’s white-ball DNA has been to deny bowling plans a quiet phase.

– India

Highest successful chase: 362/1 vs Australia (target 360) at Jaipur.

Signature traits: template chases, premium top-three who convert starts into big strides, and calm manipulation of spin in the middle overs. The finish is often less about last-over drama and more about killing a chase with an innings to spare.

– England

Highest successful chase: 364/4 vs West Indies (target 361) at Bridgetown.

Signature traits: a deep engine room of hitters stacked through No. 7, permission to attack through the middle regardless of recent wickets, and field-side awareness at small English venues and Caribbean grounds with cross-breeze.

– Australia

Highest successful chase: 359/6 vs India (target 359) at Mohali.

Signature traits: skill-based power in the top six, near-scientific reading of field placements, and an ability to keep asking the bowling captain to change a plan. Australia chase best when three batters cross fifty and one carries.

– Pakistan

Highest successful chase: 352/4 vs Australia (target 349) at Lahore.

Signature traits: anchoring mixed with flair—two controlled innings bracketing a sudden gear shift. Pakistan’s best chases read like a quiet story until they don’t.

– New Zealand

Highest successful chase: 350/9 vs Australia (target 347) at Hamilton; also 348/6 vs India (target 348) at Hamilton.

Signature traits: batting clarity against pace on skiddy pitches, mid-innings acceleration by wicketkeeper-batters, and a knack for breaking a chase into mini-battles by over and by matchup.

– Sri Lanka

Highest successful chase: 344/4 vs England (target 343) at Leeds.

Signature traits: openers who go hard in tandem, plus a traditional comfort against seam with the ball old. When the surface offers true pace-on and a fast outfield, Sri Lanka’s timing game thrives.

– Bangladesh

Highest successful chase: 322/3 vs West Indies (target 322) at Taunton.

Signature traits: structured chases anchored by a senior batter, scarcity of panic in clusters of wickets, and an instinct to stay in touch with par without burning resources too early.

– West Indies

Highest successful chase: above 330 in bilateral ODIs is rare, but the modern West Indies have pushed over 300 with room to spare on Caribbean wickets when a set top-order hitter bats deep.

Signature traits: streak hitting that collapses the chase equation instantly; when paired with efficient rotation, their ceiling is higher than the average table suggests.

– Afghanistan

Highest successful chase: past 300 in bilateral matches is increasingly common; a defining chase includes the methodical takedown of Pakistan at an Indian venue.

Signature traits: a calm core at three and four, plus finishers who sweep pace like spin through midwicket. As their top order has matured, Afghanistan’s chases have become less binary and more inevitable.

– Zimbabwe, Ireland, Netherlands, Scotland

These teams have authored some of ODI chasing’s most evocative nights: Ireland’s 329 chase against England is burned into the sport’s memory; the Netherlands have engineered one of the format’s craziest equalizers and a super-over finish at a qualifier; Scotland and Zimbabwe have repeatedly shown that targets once considered safe can buckle under one long partnership.

Highest ODI chases in World Cups

Tournament pressure changes the geometry of a pursuit. Fielding sides don’t experiment as much, captains play the long hand with their premium overs, and the team batting second often faces the scoreboard plus the bracket.

Highest successful run chase in an ODI World Cup

Pakistan’s 345 for 4 against Sri Lanka at Hyderabad stands as the tournament benchmark. It reset the ceiling for a World Cup chase and—more importantly—validated that multi-stage acceleration remains viable even under tournament stress.

Other World Cup landmark chases

- Ireland’s 329 burst past England—proof a target north of 320 could be hunted without a top-three megastar.

- Bangladesh’s 322 against West Indies—cold, clinical tempo control.

- Sri Lanka’s 313 at a time when 300 in a tournament felt terminal in many conditions.

The pattern across editions: tournament pitches have quickened and held up better under lights in several host regions, and teams have become comfortable splitting the chase into three distinct tempos rather than two. What used to be a singular “launch” phase is now often a double surge—one before the second Powerplay closes and one across the last eight overs.

Fastest successful ODI chases by run rate and overs to spare

Raw run rate in a chase demands context. A rapid pursuit of a modest target is one thing; maintaining nine-plus per over against a target beyond 320 is something else entirely.

High-run-rate chases against big targets

- India 362/1 in 43.3 overs for a target of 360 at Jaipur: par-charts from that night still circulate in coaching sessions. India turned a nine-an-over ask into a comfortable, early finish without losing shape.

- England 364/4 in 48.4 overs for a target of 361: not outrageous on the calculator, but devastating in control—never a stage where the chasing side seemed strained.

- South Africa 372/6 in Durban, crossing a 370-plus target with time and wickets to spare, underlines that modern chases thrive on a stable run rate rather than one late explosion.

Chases with many balls to spare in the 300-plus range

The elite examples tend to keep ten or more balls in hand—the real signature of a team that controlled the chase from overs 15 to 35. The best practice is almost universal now: keep wickets, keep the board moving, and trust two hitters to cash in at the death.

Highest ODI run chases by venue and country

Some venues are built for pursuit. If you’ve worked in analysis rooms for touring sides, you know the whiteboard shorthand: altitude gives you bonus carry; small square boundaries demand leg-side protection; outfields that race turn ones into twos.

Johannesburg (The Wanderers)

Altitude, hard bounce, and light air. Once the ball gets old, length becomes a liability. The 438 match taught teams to never close a chase on the off side alone; you must split fields and force captains to protect both squares.

Durban (Kingsmead)

A deceptive chasing wicket. Traditionally holds for cutters late, but when the deck is flat it becomes hard to close out. South Africa’s 372 chase was as much about field control as striking.

Nottingham (Trent Bridge)

Small straight, quick outfield. England’s most unbothered chases against stiff targets have often arrived here, where a batting unit can ride one short side and deemphasize risk.

Jaipur and Pune

Indian venues with dew that makes bowling at night a different sport. Targets above 340 stop being endpoints and become projects. The smart tactic is to protect a set batter and never let the asking rate carry a seven in the first twenty.

Bridgetown

Caribbean breeze and a boundary configuration that rewards strong wrists. England’s 360-plus chase here felt less like a chase and more like confirming a plan the dressing room already trusted.

Hamilton (Seddon Park)

Not the biggest squares; skiddy, pace-on days make stroke-play premium. New Zealand own several of the format’s most underrated chases on this ground against top-tier attacks.

Day versus day-night: handling dew, hardness, and anxiety

Day-night ODIs shift the balance late. Dew softens the ball’s grip for spinners and asks seamers to nail wet-finger skills. The chasing side must recalibrate the middle overs:

- Bat versus ball: dew inflates the value of hitting zones—especially with the slog sweep and the pick-up over midwicket. Teams use wet outfields to get the ball worked quickly beyond the hard, swinging phase.

- Field placements: captains are more defensive earlier in the chase if dew threatens. Singles flow; dots die.

- Bowling options: cutters and cross-seam become emergency levers, but only if the deck grips. Otherwise, pace-off floats become sitters in the slot.

The best chasing teams bake this into selection, favoring bowlers with late-overs experience and batters who can pierce defensive fields without aiming for the roof.

DLS and the art of a moving target

Targets modified by the DLS method stress-test communication. A dressing room with a robust DLS protocol—someone glued to the par sheet, someone else doing bowl-by-bowl recalculation—will routinely outplay a more talented side that doesn’t respect the math.

- Chasing under DLS works best when:

- The set batter knows the par after every over.

- New batters get a two-over runway with the strike farmed sensibly.

- The team resists panic if a rain break sets a steeper curve; the immediate plan is placement, not power.

Classic DLS-era chases reveal an often-overlooked truth: every single in the middle overs is an insurance policy against a sudden weather cut.

By wickets remaining: clinical versus chaotic

Some of the most revealing record chases end with a well-set batting side and seven or more wickets in hand. That tells you two things: they read the pitch perfectly, and they cooked the run rate without headless risk.

High targets chased with many wickets in hand

- India’s 362/1 at Jaipur is the gold standard; nine wickets in hand at the finish against a 360 chase speaks to total control.

- Sri Lanka’s 344/4 at Leeds: a day when the openers decided the match inside 25 overs and everything else was bookkeeping.

High targets chased with minimal wickets in hand

438 remains the apex of high-wire drama. The one-wicket finish doesn’t just tell you about tension; it tells you about a side that kept punching after the overs cushion was gone.

A batting order’s shape matters here. Modern sides select seven plausible batters, trusting No. 7 to carry near-four-over workloads if needed. Once you grasp that, the psychology of a late collapse looks different: it’s a correction at the edge, not a strategic failure.

How ODI run chases have transformed

If you chart successful chases across 50-over cricket, the curve doesn’t just slope upward; it changes character at several distinct inflection points.

- The powerplay era: Fielding restrictions taught top orders to exploit width and length fearlessly. This normalized 60‑plus powerplays without risky lofted shots.

- The middle-over revolution: Once teams learned to choke spin with low-risk boundary options—sweep variants, aerial clips over midwicket, and the EAB (everything-around-the-bat) nudges to third and fine—chases no longer stalled between overs 15 and 35.

- The death-overs calculus: Finishing isn’t about sixes. It’s about seeing the field at head height, manipulating angles, and forcing a bowler to miss the yorker by the width of a bat. The best finishers—regardless of language or domestic system—talk about clarity, not bravery.

- Data and matchups: Dressing rooms moved from hunch to evidence. If a left-arm quick hates bowling to a particular right-hander from one end with one boundary short, the matchup is engineered. The modern chase is a many-variabled choice tree, not just a run rate.

Notable record chases: anatomy of a pursuit

A few matches are masterclasses. If you’re teaching a youth pro or briefing a commentary booth, these are the pursuits to rewatch in full.

South Africa 438/9 vs Australia, target 435, Johannesburg

- Tactics: relentless pace-on hitting in altitude; commit early to short-side options; protect someone for the last two overs.

- Moment: Gibbs launching from 50s into 170s with risk managed by field recognition rather than muscle brawn.

- Lesson: in flat, fast conditions, the old rule of “wickets in hand at 40 overs” can be replaced by “momentum in hand at 25.”

South Africa 372/6 vs Australia, target 372, Durban

- Tactics: bites of acceleration rather than one surge. Miller’s finish wasn’t a cameo; it was a controlled demolition of lengths that had worked earlier.

- Lesson: on decks that hold true, a pro can score at nine-an-over for 15 overs without visible strain.

England 364/4 vs West Indies, target 361, Bridgetown

- Tactics: powerplay attack plus no stall across spin; Root’s risk just below aggression threshold; keep an over ahead of the par.

- Lesson: a chase can be suffocated from the other end—singles mount pressure on the bowler more than on the batting side if fields are stretched.

India 362/1 vs Australia, target 360, Jaipur

- Tactics: control the chase with batting first principles; never let required rate touch crisis territory; take full toll of the fifth bowler.

- Moment: Kohli’s 50 off 52 balls—the most instructive hundred in a modern chase for how it married tempo with mastery of the gaps.

- Lesson: separation of duties—when two top-order batters share the table cleanly, the chase becomes a batting practice of angles.

Pakistan 352/4 vs Australia, target 349, Lahore

- Tactics: anchor plus anchor plus launch. Imam’s spine, Babar’s command, late acceleration through the V.

- Lesson: you can outlast a big target without theatrics if your two best technical batters own the middle overs.

New Zealand 350/9 vs Australia, target 347, Hamilton

- Tactics: hold nerve late; value two shots against an overpitched death ball; survive the squeeze with smart twos.

- Lesson: the difference between a famous chase and a famous heartbreak is how many dot balls you accept in overs 46–48.

Sri Lanka 344/4 vs England, target 343, Leeds

- Tactics: dual openers stepping on the pedal in sync; no drag on the scoreboard; bowlers forced to go searching when the surface offers none.

- Lesson: sometimes the best finish is no finish—close a chase early so the last ten overs are a parade.

Why some venues produce more successful chases than others

It’s not only about small boundaries and dew. It’s about the margin for error for bowlers and the clarity that gives batters.

- Ball behavior: When the ball doesn’t grip, cutters become floaters and yorkers become low full tosses. Chasers plan to sit on the short-of-a-length ball and punish anything within their reach. Wickets that scuff but don’t split are ideal.

- Outfield speed: A lightning outfield can gift 25–30 free runs in a chase. Sides measure outfield speed in warm-ups with boundary drills and throw-down simulations.

- Square dimensions: Coaches map the ground in the team room. Get two batters who hit opposite sides well—one loves the pickup over deep midwicket, the other threads the cover wedge. It forces captains into ugly compromises.

- Wind lanes: Grounds with a constant cross-breeze turn lofted drives into misreads for fielders and misjudgments for bowlers. Teams with caps on risk often loosen here.

How captains and coaches measure a chase in real time

Forget the broadcast worm for a moment. Inside the dressing room, the signals are more granular.

- Par sheets and phase targets: Instead of “we need 120 in the last ten,” the group uses micro-targets: “ten an over through two overs, one risk shot per over maximum, keep four in the bank for over 49.”

- Bowler mapping: The captain marks which overs each opposition bowler likely has left, plus ends preferred. If the short side flips, so does the plan.

- Batter matching: Coaches align a batter’s best scoring arcs to the incoming bowlers. Matchups decide who takes strike even more than who is set.

- Crisis posture: Lose two in two? The rule for elite teams is the same: take six singles and one boundary in the next over. Reclaim tempo before you reclaim dominance.

Patterns in the data: what “impossible” looks like now

- Targets once seen as par-defended—320, 330—are now deeply chaseable on flat surfaces with an average batting unit. If a team is 150 without significant damage at the halfway mark, the fielding side often struggles to reassert control.

- The point of no return, in clean conditions, has crept up above 370. Even there, modern sides think in chunks of 30 runs rather than one big mountain.

- Six-hitting remains a highlight, but the most consistent predictor of a successful large chase is boundaries between overs 11 and 35. When a side logs eight or more fours in that period without losing three wickets, they are almost always alive late.

The skill set of a great ODI chaser today

- Powerplay humility: Take what’s on offer; punish only the ball you own. A 55/0 powerplay can build a 360 platform.

- Spin literacy: Sweep both ways, open the off side with late cuts, and rotate without cheating across the crease.

- Death discipline: See the field, not the ball. Decide your scoring stroke before the bowler runs in; trust the pre-ball choice until proven wrong.

- Emotional management: Big chases blow hot and cold. The team that returns fastest to process after a wicket wins the last five overs.

Adjacent records that define context

- Highest team totals in ODIs provide one half of the chase equation; the other half is the DNA of a side when the line is outside comfort range. Cross-traffic between these lists is common; the best batting sides push the ceiling both ways.

- Highest unsuccessful chases often contain the best blueprints for next time. Watching a side finish 15 short tells you how a future unit will reshape overs 35–45.

- Highest individual scores in an ODI chase don’t always marry with a successful team result; the greatest chases distribute runs expertly.

World Cup-only chases: how they feel different

- Bowling captains hoard premium overs for too long, and chasers who read this reach for the kill early—particularly overs 30–40 when the second-new-ball juice is fading.

- Crowd pressure changes kick points. The home side may prioritize a silent middle phase just to calm the stands; the away side may embrace chaos.

- Selection compromises matter; a team going thin on a sixth bowling option is essentially asking to defend ten shorter overs.

Most recent trends: what the last cycle tells us

- The bar for what counts as “impossible” keeps creeping upward, but not as steeply as it did during the power-hitting boom at its loudest. Modern attacks have re-learned length variation and created more dismissals with a scrambled seam than with sheer pace.

- Teams winning the toss at venues with reliable dew still think chase first, but hybrid pitches and rolled grass have curbed some of the nighttime advantage.

- Batting depth is a selection non-negotiable. Extra bowling is necessary, but not at the expense of a No. 7 who can score at seven-an-over on command.

Coaching notes: how to plan a big chase

Pre-match

- Map boundary value by side and by bowler end.

- Assign overs 41–50 to specific hitters based on bowling projections.

- Decide the “go-zones” for overs 14–20 and 28–34 ahead of time.

In-match

- Communicate par after every over to set batters. Keep the dugout chatter quiet and precise.

- If the required rate rises above nine with two set, resist slog mode; reinforce strike rotation and punish width.

- If weather looms, compute the next two overs as if they’re your last two—don’t save gun batters for a finish that might be cut.

Post-match review

- Grade the chase not by result but by phase execution: powerplay, spin window, seam return, and death.

- Treat dot-ball clusters as coaching gold. Find the pattern and fix it in net scenarios.

Frequently asked facts

- What is the highest successful run chase in ODI history?

South Africa’s 438 for 9 against Australia at Johannesburg, chasing 435. - Which team owns the most 350-plus successful ODI chases?

South Africa and England share a strong presence above 350, with India and Australia close behind. - What is the highest successful run chase in the ODI World Cup?

Pakistan’s 345 for 4 against Sri Lanka at Hyderabad. - How many times has a target of 350 or more been chased successfully?

Multiple times across formats and venues in the modern era; the count grows steadily with each international cycle as batting depth and matchups improve. - What is India’s highest successful run chase in ODIs?

362 for 1 against Australia at Jaipur, chasing 360. - What is Australia’s highest successful run chase in ODIs?

359 for 6 against India at Mohali, chasing 359. - What is England’s highest successful run chase in ODIs?

364 for 4 against West Indies at Bridgetown, chasing 361. - What is New Zealand’s highest successful run chase in ODIs?

350 for 9 against Australia at Hamilton and 348 for 6 against India at the same venue, both landmark pursuits. - Which venue has produced the most iconic high chases?

Johannesburg for altitude-fueled hitting; Nottingham, Jaipur, Hamilton, Bridgetown, and Durban each house defining chases and surface traits that favor pursuit. - What is the highest target chased without losing a wicket?

Elite examples sit around the mid-200s into the low-300s range, with India and Sri Lanka among the sides to have finished large pursuits with minimal or no wickets down on true decks.

The human side of a big chase

You can plot the run rate and map the worm, but big chases make you feel it. There is a mood that settles over a ground when a pursuing side refuses to submit to the math. The dressing room oxygen dips a degree; the noise in the stands turns from roar to hum; a bowling unit that once imagined the total as unscaleable starts to bowl to ghosts.

The batters don’t see numbers. They see fields. That’s the secret. A great chase never becomes a pursuit of a number; it becomes a sequence of fields you defeat, one after the other, until the target is a single swing or a quiet nudge to the sweeper. You remember the headline—the 438, the 372, the 364—but the essence lives in the choices: the leave on a hard length at eight an over, the single stolen to long-off, the trust to take the spinner over the top because the breeze is with you. That’s how the best teams write their names into the top line of a list like this. Not with bravado, but with clarity.

Closing notes

ODI chasing has entered an age where ceiling and consistency coexist. Targets that once came with a handshake now come with a blueprint. South Africa’s thunderclap at Johannesburg still sits at the summit, a monument to audacity and calculation. Everything since has been a refinement—and an invitation to go higher.

For deeper stat dives, match logs, and filterable tables by team, venue, decade, wickets in hand, and DLS involvement, the standard professional references remain the cricket databases maintained by global scorecard providers and governing bodies. These archives capture every new entry the moment a side dares to turn a big number into just another chase.

Related posts:

Top ipl team most fans: Followers, Engagement, Trends

Guide: smallest cricket stadium in india - Capacity vs Boundary

Compare ipl vs psl: scale, money, competitiveness

The king of ipl: Data-Backed Verdict

Fastest 50 IPL: All‑Time List, Tactical Deep Dive

Best Cricket Betting Apps in India: UPI, Live Bets & Fast Payouts

Angad Mehra

- Angad Mehra is an avid cricket analyst and sports writer who pays attention to betting patterns and match specifics. Angad has years of experience writing, covering both Indian and international cricket. He explains stats, odds, and strategies in a clear, simple manner that resonates with fans. Readers trust Angad’s articles to keep them ahead of the game whether on or off the field. Off the field, you can find him either tracking live scores ball by ball or debating IPL lineup changes.

Latest entries

GeneralNovember 1, 2025Cricket Prince: Who’s the Heir — Lara, Gill, or Babar?

GeneralNovember 1, 2025Cricket Prince: Who’s the Heir — Lara, Gill, or Babar? GeneralOctober 31, 2025T20 Highest Score Guide: Team Totals, Records & Context

GeneralOctober 31, 2025T20 Highest Score Guide: Team Totals, Records & Context GeneralOctober 29, 2025Youngest cricketer in India: Complete Guide to Records & Pathways

GeneralOctober 29, 2025Youngest cricketer in India: Complete Guide to Records & Pathways GeneralOctober 27, 2025Psl winners list: Season‑by‑season champions & finals

GeneralOctober 27, 2025Psl winners list: Season‑by‑season champions & finals